Lilliana Mason. Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity. University of Chicago Press, 2018. (183 pages)

REFLECTIONS

Allow me to sum up the most important takeaways if we are going to have a civil society:

- Do not identify with a party. Group identity theory is a powerful force in our psychology that exacerbates irrationality.

- Choose anxiety over anger. Anger blinds your thinking and suppresses your compassion. Anxiety initiates a more creative process, the desire for solutions.

- Ground your activism in conviction, not reaction. Reverse the impulse to only be “active” when outraged.

- Diversify media input, or better yet, scrutinize media altogether. What we consume shapes our views.

- Affirm everyone’s (including your own) self-worth. Fear and insecurity are the driving factors in polarization.

If we can do that, our society, our democracy, and our own personal well-being would all be better off.

We are still in the thick of a socio-political morass that is driving polarization, increasing outrage, and dissolving the norms of our society, the fabric of our nation. The solution to this is not to become outraged and to blame, but rather to slow down and understand. It is to recognize that we all are perhaps victims of our own psychologies, exacerbated by our own systems. It may be that we are reaping the unintended consequences of our own solutions, efforts we once put in place to solve different problems then which created new and more pernicious maladies now. Therefore, we should consider carefully that our political opponent is not our enemy. The impulse to call them our “enemy” is the enemy.

Uncivil Agreement is an important and insightful book on the forces that shape our psychologies, identities, and our political persuasions. It is also hopeful and helpful in that it charts a pathway forward (as listed in the 5 takeaways listed above). These are the disciplines we can leverage now that could save us from the decline of our cognition at the hands of our own outrage, if we would simply have the socio-political and emotional will to live this way publicly. I am deeply grateful for Mason’s work, and for the astute attention paid to our psychologies. I commend this to you for your consideration in hopes of a more civil and less polarized body politic.

NOTES

ONE / Identity-Based Democracy

cf. “The Robbers Cave” experiment by Muzafer Sherif

The boys at Robbers Cave needed nothing but isolation and competition to almost instantaneously consider the other team to be “dirty bums,” to hold negative stereotypes about them, to avoid social contact with them, and to overestimate their own group’s abilities. In very basic ways, group identification and conflict change the way we think and feel about ourselves and our opponents. (2)

As the parties have grown racially, religiously, and socially distant from one another, a new kind of social discord has been growing. The increasing political divide has allowed political, public, electoral, and national norms to be broken with little to no consequence. The norms of racial, religious, and cultural respect have deteriorated. Partisan battles have helped organize Americans’ distrust for “the other” in politically powerful ways. In this political environment, a candidate who picks up the banner of “us versus them” and “winning versus losing” is almost guaranteed to tap into a current of resentment and anger across racial, religious, and cultural lines, which have recently divided neatly by party. (3)

…members of both parties negatively stereotype members of the opposing party, and the extent of this partisan stereotyping has increased by 50 percent between 1960 and 2010. They view the other party as more extreme than their own, while they view their own party as not at all extreme. …for the first time in more than twenty years, majorities of Democrats and Republicans hold very unfavorable views of their partisan opponents. American partisans today prefer to live in neighborhoods with members of their own party, expressing less satisfaction with their neighborhood when told that opposing partisans live there. (3)

| Increasing numbers of partisans don’t want party leaders to compromise, blaming the other party for all incivility in the government (Wlf, Strachan, and Shea 2012), even though, according to a 2014 Pew poll, 71 percent of Americans believe that a failure of the two parties to work together would harm the nation “a lot” (Pew 2014). Yet, as a 2016 Pew poll reports, “Most partisans say that, when it comes to how Democrats and Republicans should address the most important issues facing the country, their party should get more out of the deal” (Pew 2016). (3)

| Democrats and Republicans also view objective economic conditions differently, depending on which party is in power (Enns and McAvoy 2012). (3)

Group victory is a powerful prize, and American partisans have increasingly seen that goal as more important than the practical matters of governing a nation. (4)

This book looks at the effects of our group identities, particularly our partisan identities and other party-linked identities, on our abilities to fairly judge political opponents, to view politics with a reasoned and unbiased eye, and to evaluate objective reality. I explain how natural and easy it can be for Democrats and Republicans to see the world through partisan eyes and why we are increasingly doing so. …American partisans today are prone to stereotyping, prejudice, and emotional volatility, a phenomenon that I refer to as social polarization. Rather than simply disagreeing over policy outcomes, we are increasingly blind to our commonalities, seeing each other only as two teams fighting for a trophy. (4)

| Social polarization is defined by prejudice, anger, and activism on behalf of that prejudice and anger. …our conflicts are largely over who we think we are rather than over reasoned differences of opinion. (4)

The First Step Is to Admit There Is a Problem

cf. “Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System: A Report of the Committee on Political Parties,” APSA, 1950

Parties, therefore, simplify politics for people who rightly do not have the time or resources to be political experts. (5)

When the report was released (the 81st Congress, 1950), the average Democrat in the House was less than 3 standard deviations away from the average Republican. In the Senate, the distance was less than 2.25 standard deviations. …by 108th Congress (2003-4), the average party members were separated by more than 5 standard deviations in the House and almost 5 standard deviations int he Senate. – Sean Theriault, Party Polarization in Congress, p.226

This acts as a heuristic, a cognitive shortcut that allows voters to make choices that are informed by some helpful truth. (5)

Even better, when people feel linked to a party, they tend to more often participate in politics,… Partisanship, then, is one important link between individuals and political action. (5)

It should be clarified at the start that this book is not opposed to all partisanship, all parties, party systems, or even partisan discord. There has been, and can be, a responsible two-party system in American politics. Instead, this book explains how the responsible part of a two-party system can be called into question when the electorate itself begins to lose perspective on the differences between opponents and enemies. (6)

[via: But isn’t the whole point of this, and other work, is that this conclusion is inevitable?]

Parties can help citizens construct and maintain a functioning government. But if citizens use parties as a social dividing line, those same parties can keep citizens from agreeing to the compromise and cooperation that necessarily define democracy. (6)

| Partisanship grows irresponsible when it sends partisans into action for the wrong reasons. Activism is almost always a good thing, particularly when we have so often worried about an apathetic electorate. But if the electorate is moved to action by a desire for victory that exceeds their desire for the greater good, the action is no longer, as regards the general electorate, responsible. (6)

| In the chapters that follow, I demonstrate how partisan, ideological, religious, and racial identities have, in recent decades, moved into strong alignment, or have become “sorted.” (6)

In line with Bill Bishop’s (2009) book The Big Sort, I argue that this new alignment has degraded the cross-cutting social ties that once allowed for partisan compromise. This has generated an electorate that is more biased against and angry at opponents, and more willing to act on that bias and anger. (6)

Here is the other threat to liberty that Alexis de Tocqueville and the ancient philosophers warned about: that the people in a democracy, excited, angry and unconstrained, might run roughshod over even the institutions created to preserve their freedoms. – Robert Kagan, 2016

Cross-Pressures

…“cross-cutting cleavages.” These are attitudes or identities that are not commonly found the partisan’s party. If a person is a member of one party and also a member of a social group that is generally associated with the opposing party, the effect of partisanship on bias and action can be dampened. However, if a person is a member of one party and also a member of another social group that is mostly made up of fellow partisans, the biasing and polarizing effect of partisanship can grow stronger. (7)

Not only are cross-pressured voters a source of popular responsiveness, they are also a buffer against social polarization. (8)

Here, rather than looking at a clash between partisans and their evaluations of their own party, I look at the relationship between partisan identities and other social identities that are to greater or lesser degrees associated with the party. (8)

| The reason I focus on the clash of identities, rather than the clash between party and attitudes, is that social identities have a special power to affect behavior. … Partisans are responsive to the identities and ideas o the people around them. (8)

| Second, and more central to the theme of the book, the identities them-(8)selves have psychological effects of their own. (9)

The Origins of Group Conflict

Humans are hardwired to cling to social groups. There are a few good reasons to do so. First, without a sense of social cohesion, we would have had a hard time creating societies and civilizations. Second, and even more basic, humans have a need to categorize. … This includes categorizing people. Third, our social categories don’t simply help us understand our social environment, they also help us understand ourselves and our place in the world. Once we are part of a group, we know how to identify ourselves in relation to the other people in our society, and we derive an emotional connection and a sense of well-being from being group members. (9)

However, simple cohesion creates boundaries between those in our group and those outside it. (9) Marilynn Brewer has argued that as human beings we have two competing social needs: one for inclusion and one for differentiation. … If ew create clear boundaries between our group and outsiders, we can satisfy our needs for both inclusion and exclusion. This means that humans are motivated not only to form groups but (9) to form exclusive groups. …people automatically tend to spend time with people like themselves. Much of the reasoning for this is simple convenience. [Gordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice, 1954] explains, “it requires less effort to deal with people who have similar presuppositions”. However, once this separation occurs, we are psychologically inclined to evaluate our various groups with an unrealistic view of their relative merits. (10)

Minimal Group Paradigm

The ingroup bias that results from even minimal group membership is very deeply rooted in human psychological function and is perhaps impossible to escape. … Simply being part of a group causes ingroup favoritism, with or without objective competition between the groups over real resources. Even when there is nothing to fight over, group members want to win. (11)

[Henri] Tajfel points out that one of the most important lessons of the minimal group experiments is that when the subjects are given a choice between providing the maximum benefit to all of the subjects, including those in their own group, or gaining less benefits for their group but seeing their team win, “it is the winning that seems more important to them”. (11)

The privileging of victory over the greater good is a natural outcome of even the most meaningless group label. (12)

[via: We’re screwed.]

Physical Evidence of Group Attachment

Avenanti, Sirigu, and Aglioti (2010) showed respondents video of hands being pricked by pins. People tended to unconsciously twitch their own hand when watching these videos, except when the hand belonged to a member of a racial outgroup. (12)

| Scheepers and Derks (2016) explained that it is possible to observe changes in brain activity within 200 milliseconds after a face is shown to a person, and that these changes depend on the social category of the face. Furthermore, they found that people who identify with a group use the same parts of their brain to process group-related and self-related information, but a different part of the brain to process outgroup-related information. (12)

Hobson and Inzlicht (2016) found that when learning a new task, a person will learn more slowly if he or she is being observed by an outgroup member. (12)

| You can find evidence of group membership in saliva. Sampasivam et al. (2016) found that when people’s group identity is threatened, they secrete higher levels of cortisol in their saliva, indicating stress. (12)

People’s brains respond similarly when people are sad and when they are observing a sad ingroup member, but when they are observing a sad outgroup member, their brains respond by activating areas of positive emotion. (12)

…favoring the ingroup is not a conscious choice. Instead, people automatically and preferentially process information related to their ingroup over the outgroup. – Scheepers and Derks (2016)

Invented Conflicts

…group members “easily exaggerate the degree of difference between groups, and readily misunderstand the grounds for it. And, perhaps most important of all, the separateness may lead to genuine conflicts of interest as well as to many imaginary conflicts”. [Allport, 1954] (13)

Motivated reasoning is not exactly “inventing” conflicts, but it is the brain’s way of making preexisting attitudes easier to believe. This occurs not by choice, but at a subconscious level in the (13) brain, where the things a person wants to believe are easier to locate than the things that contradict a person’s worldview. … The human brain prefers not to revise erroneous beliefs about opponents. (14)

The trouble arises when party competitions grow increasingly impassioned due to the inclusion of additional, nonpartisan social identities in every partisan conflict. … This is no longer a single social identity. Partisanship can now be thought of as a mega-identity, with all the psychological and behavioral magnifications that implies. (14)

Why Does This Matter

In this binary tribal world, where everything is at stake, everything is in play, there is no room for quibbles about character, or truth, or principles. If everything–the Supreme Court, the fate of Western civilization, the survival of the planet–depends on tribal victory, then neither individuals nor ideas can be determinative. – Charles Sykes, “Charlie Sykes on Where the Right Went Wrong”

…in the extreme this consistency can also be a signal that American voters are no longer thinking independently, that they are less open to alternative ideas. (15)

The second effect is the main concern of this book, and that is the power of social identities to affect party evaluations, levels of anger, and political activism, independently of a person’s policy opinions. When megaparties form, social polarization increases in the American electorate. Both social and issue-based polarization have recently been shown to decrease public desire for compromise, decrease the impact of substantive information on policy opinions, increase income inequality, discourage economic investment and output, increase unemployment, and inhibit public understanding of objective economic information, among other things. (15)

As citizens, we may not be able to change the primary rules or tone down the partisan media, but we can begin to understand how much of our political behavior is driven by forces that are not rational or fair-minded. This book lays out the evidence for the current state of social polarization, in which our political identities are running circles around our policy preferences in driving our political thoughts, emotions, and actions. I explain how this came to be, illustrate the extent of the problem, and offer some suggestions on how to bring American politics back to a state of civil competition, rather than a state of victory-centric conflict. (16)

TWO / Using Old Words in New Ways

In the social-scientific study of politics the term polarization traditionally describes an expansion of the distance between the issue positions of Democrats and Republicans. …sorting is usually defined as an increasing alignment between party and ideology, where ideology indicates a set of issue positions or values. (17)

In this book, one major goal is to make the point that each of these terms–polarization, sorting, and ideology–include within them both a social meaning and an issue-based meaning. The social definition focuses on people’s feelings of social attachment to a group of others, not their policy attitudes. The issue-based definition is limited to individual policy attitudes, excluding group attachments. The fact that these two elements can be separated from each other at all is the basis on which this entire argument rests. (17)

Social polarization refers to an increasing social distance between Democrats and Republicans. This is made up of three phenomena: increased partisan bias, increased emotional reactivity, and increased activism. Issue-based polarization is closer to the tra-(17)ditional understanding of the term polarization, and indicates an increasing distance between the average issue positions of Democrats and Republicans. (18)

…identity-based (or symbolic) ideology is the sense of belonging to the groups called liberal and conservative, regardless of policy attitudes. Issue-based (or operational) ideology is a set of policy attitudes and the extent to which they tend to be on the liberal or conservative end of the spectrum. (18)

Social sorting involves an increasing social homogeneity within each party, such that religious, racial, and ideological divides tend to line up along partisan lines. Issue-based sorting is closer to the traditional understanding of sorting, meaning that Democrats hold liberal issue positions and Republicans hold conservative issue positions. (18)

| The difference between issue-based sorting and issue-based polarization is simply that issue-based sorting occurs when partisans hold policy preferences that are increasingly consistent with their party’s positions. There are fewer cross-cutting policy attitudes. Issue-based polarization involves the policy preferences of Democrats and Republicans growing increasingly bimodal and moving toward extremely liberal or conservative policy choices. (18)

A Different Identity Politics

…collective identity becomes politically relevant when people who share a specific identity take part in political action on behalf of that collective. – Klandermans (2014)

A single group identity can have powerful effects, but multiple identities all playing for the same team can lead to a very deep social and even cultural divide. (19)

Identity and Policy

…the “folk theory” of democracy. (20)

Decades of social-scientific evidence show that voting behavior is primarily a product of inherited partisan loyalties, social identities and symbolic attachments. Over time, engaged citizens may construct policy preferences and ideologies that rationalize their choice,s but those issues are seldom fundamental. – Achen and Bartels (2016b)

More often than not, citi-(20)zens do not choose which party to support based on policy opinion; they alter their policy opinion according to which party they support. (21)

Identity and Ideology

…symbolic ideology and operational ideology. … Americans, it seems, are generally liberal in our policy positions and values, but generally conservative in what we like to call ourselves. … It is important to understand that American ideological identities are not synonymous with policy preferences. (22)

Three Elements of Social Polarization

Social identities generate distinct psychological and behavioral outcomes. Three of these make up social polarization. (23)

| First, in line with Tajfel and Turner’s social identity theory, when two groups are in a zero-sum competition, they treat each other with bias and even prejudice. The first element of social polarization is therefore partisan prejudice. (23)

| Second, those who identify with a social group are more likely to take action to defend it. (23)

Third, one outgrowth of social identity theory is intergroup emotions theory, which specifies that group members can and do feel emotions on behalf of the group. (23)

THREE / A Brief History of Social Sorting

The chief oppositions which occur in society are between individuals, sexes, ages, races, nationalities, sections, classes, political parties and religious sects. Several such may be in full swing at the same time, but the more numerous they are the less menacing is any one. Every species of conflict interferes with every other species in society at the same time, save only when their lines of cleavage coincide; in which case they reinforce one another. … A society, therefore, which is riven by a dozen oppositions along lines running in every direction, may actually be in less danger of being torn with violence or falling to pieces than one split along just one line. – Edward Alsworth Ross, The Principles of Sociology

The sorting of American social groups into two partisan camps has intensified in recent decades, leading to a distinct decrease in the number of cross-cutting cleavages. Social cleavages today have become significantly linked to our two political parties, with each party taking consistent sides in racial, religious, ideological, and cultural divides. (25)

Ideological Sorting

Specifying ideology as a social identity makes it clear that identity-based ideological sorting is increasing more robustly than the traditional measure of ideology can indicate. (28)

Figure 3.2. Identity-based Ideology

Note: Data drawn from the American National Election Studies from 1972, 1992, and 2000. Democrats and Republicans include independents who lean toward one party. Vertical axis represents the percentage of Democrats/Republicans who identify with liberals/conservatives, respectively.

More than simply disagreeing, Democrats and Republicans are feeling like very different kinds of people. (31)

Theories of Sorting

A number of theories attempt to explain issue-based sorting, beginning with an issue-based story and ending with a more complete sorting of multiple social identities along partisan lines. (31)

| The more popular explanation for issue-based sorting involves the changes in the Democratic Party that occurred as a result of the civil rights movement, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. (31)

This caused a deep division within the Democratic Party, which was papered over for a few years but reopened in 1954 after the Supreme Court ruled against segregation in Brown v. Board of Education. (32)

The new alignment of the Democratic Party with the rights of blacks caused vast numbers of conservative white southern Democrats to move gradually to the Republican Party, leaving average Democrats more liberal and average Republicans more conservative. This racial-policy shift in the Democratic Party and subsequent realignment of conservative southern Democrats is generally understood to be one major reason that Democrats and Republicans today are more ideologically pure than they were in 1950. In this explanation, a racial-policy change in the Democratic Party is the root of all of today’s partisan polarization. In some sense, this may be true. Without the civil rights policy change, nothing that came later would likely have happened in the same way. But if a policy change started the path to a more socially sorted nation, the effects of that change drew American politics further away from policy and toward an increasingly social partisan divide. (32)

Social Sorting

cf. the Christian Coalition; 1989.

Gradually, the religious/secular divide was added to the growing list of social cleavages drawing the parties apart. (33)

Figure 3.4. Social-group sorting

Note: Bars represent the difference between the percentage of group members in the Republican Party and the percentage of group members in the Democratic Party (including partisan leaners). Income percentile is the difference between the mean income percentile of Republicans and Democrats. Data are drawn from the ANES cumulative data file for teh 1952, 1972, and 1992 graphs (fully weighted) and from the 2012 ANES (fully weighted) for the 2012 graph. There is also a gender gap between the parties, but this does not follow a clear pattern over time. Though Democrats were slightly more male (by 3 points) in 1952, Republicans have been consistently more male ever since, with a partisan gap of 4 points in 1972, 10 points in 1992, and 7 points in 2012.

…by far the most powerful social divide between the parties, rivaling the difference in ideology, was race. (37)

Identity-Based Social Sorting

Many of the social groups represented in figure 3.4 are essentially ascribed groups: race, southern residence, and income percentile are objective facts about a person. (38)

People, however, can also associate with a group on a subjective basis, by feeling some psychological sense of attachment to the group. These subjective group identities have been found to generate more loyalty from group members than objective group memberships, and therefore to have greater effects on individual behavior and intergroup relations (Huddy 2001). (38)

Figure 3.5. Identity-based social sorting

Note: Bars represent the difference between the percentage of Republicans who claimed to feel identified with each group minus the percentage of Democrats who did so (including partisan leaners). Data drawn from the ANES data files of 1972, 1992, and 2000.

As the parties became more homogeneous in ideology, race, class, geography, and religion, partisans on both sides felt increasingly connected to the groups that divided them. (40)

Sorting Made Easy

Though a racial-policy divide may ahve started the trend in social sorting, it was not the sole culprit. Social sorting has its roots in a few separate developments. (41)

| First, the issue-based division of the Democratic Party was accompanied by a providential change in American civil society. As Bill Bishop argues in his book The Big Sort (2009), the 1960s and 1970s saw a large decline in trust in government among both Democrats and Republicans–so large that it encouraged citizens to detach from their parties. … Not only did Americas lose trust in their parties, they lost trust in all institutions, resulting in a decline in civic engagement. … Americans began to grow more isolated and independent, and their political ties loosened. (41)

| This social loosening freed Americans to rearrange their partisan, social, and civic affiliations. It also, however, led Americans to feel increasingly detached from their communities and country, and compelled them to seek comfort in increasingly homogeneous neighborhoods, towns, and churches, causing American citizens to sort themselves into geographically isolated groups taht shared their culture, values, race, and politics. They disengaged from their old, community-centered groups and formed new affiliations, tailored exactly to meet their needs. (41)

The second force to contribute to social sorting, however, was the relationship between citizens and their party leaders. While citizens had been disengaging and socially segregating, the Democratic and Republican parties had been changing to provide clearer partisan, ideological, and social cues to the electorate, particularly on the Republican side. …although social sorting may have begun with a split in the Democratic Party, it was the solidification of the Republican Party into religious, middle-/upper-class, and white categories that increasingly led to a more socially sorted and divided electorate. Due to the clearer distinction between the parties, Americans had far more simple cues to follow. These cues helped citizens to understand that a highly religious Christian who is also wealthy and white will feel most at home among Republicans. Similarly, a secular, less-wealthy, black person will feel more comfortable surrounding herself with Democrats. The parties, by providing increasingly clear cues, have helped Americans to know which party is their own. (42)

| A third stimulus toward social sorting was a growing diversity of media sources. (42)

We have gone from two parties that are a little bit different in a lot of ways to two parties that are very different in a few powerful ways. (43)

Cultural Differences

The national decline in fertility and increase in the age of marriage that has occurred since the 1950s has been limited mostly to the “Blue” states. The “Red” states have comparatively higher levels of fertility and are married at younger ages (Cahn and Carbone 2010). (43)

The parties are divided in what they watch on television. … The correlation between Trump votes and “fandom” for the show Duck Dynasty (a Christian-value-based hunting show) was higher than for any other show. In fact, Duck Dynasty viewing was more predictive of a Trump vote in 2016 than it was of a Bush vote in 2000 (Katz 2016). Family Guy, an animated sitcom, was more correlated with 2016 (43) Hillary Clinton support than any other show. (44)

The makeup of the two parties has changed a great deal in the past sixty years, increasing the social distance between them. Partisans have less and less in common. Fewer cross-cutting cleavages remain to link the parties together and allow the understanding, communication, and compromise necessary to fuel the American electorate, and, by extension, the American government. Democrats and Republicans have grown so different from each other that cooperation is receding as a perceived value. When two teams grow so distinct and isolated from each other, the status of the teams themselves grows in importance. The functional outcomes of governing matter less. The sorting of our identities into partisan camps has allowed these identities to increasingly drive polarized political behavior, thought, and emotion. (44)

FOUR / Partisan Prejudice

What Is Partisanship?

In the middle of the last century, political scientists and sociologists tended toward the idea of partisanship as a distinctly social phe-(45)nomenon. (46)

A person thinks politically, as he is, socially – Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet (1944)

In 1960, Angus Campbell and his colleagues at the University of Michigan published The American Voter, which described partisan identification as a “psychological identification” and an “affective orientation.” (46)

In 2002, Green, Palmquist, and Schickler likened partisan identity to religious identity, a social-group membership that is acquired early in life and acts as an organizing force in an individual’s sense of identity and self, driving action and decision-making. (46)

The Psychological Effects of Party Identity

It is nearly impossible in most natural social situations to distinguish between discriminatory intergroup behavior based on real or perceived conflict of ‘objective’ interests between the groups and discrimination based on attempts to establish a positively valued distinctiveness for one’s own group. – Tajfel and Turner (1979) (46)

In other words, though the parties are competing for real interests, they are also competing because (47) it just feels good to win. (48)

Members of the Republican Party were willing to significantly damage the greater good of the nation in order to improve their partisan “brand.” It seems crazy, but it’s not. (49)

The work of Tajfel and Turner (1979) has grown into what is now known as social identity theory. They describe a social identity as “those aspects of an individual’s self-image that drive from the social categories to which he perceives himself as belonging” (40; emphasis added). Being part of a group informs each person’s self-image. Part of the reason for the deep and enduring existence of ingroup bias and the quest for group victory is that people are compelled to think of their groups as better than others. Without that, they themselves feel inferior. (49)

There is something inherent in a group identity that causes group members to be biased against their opponents. All of the political arguments over taxes, welfare, abortion, compassion, responsibility, and the ACA are built on a base of automatic and primal feelings that compel partisans to believe that their group is right, regardless of the content of the discussion. (50)

I call this prejudice because it is the element of the group identity that is the most visceral and tribal, and in this sense it is indistinguishable from the base motive that drives racial prejudice or religious prejudice. (50)

A degree of antipathy–at least if it is not personal–may reflect principled disagreement, not prejudice at all. But there is a large difference between a degree of antipathy and the forms of partyism we are now observing” (10. – Cass Sunstein (2015)

Warm Feelings

Figure 4.1. Warmth bias and policy extremity over time

Note: Warmth bias is the absolute difference between each respondent’s thermometer rating of the Democratic and Republican parties. Policy extremity is an index of six issues including abortion policy, government services versus spending, government health insurance, government aid to minorities, government employment protections, and defense spending. Each issue is folded in half so that higher scores represent more extreme positions on both ends of the spectrum. The six folded issue scales are then combined into an index. Data are drawn from the ANES cumulative file through 2012 (fully weighted), using only observations for which answers are available for all six issues.

Party affiliation today means that a partisan cares a great deal about one party being the winner. Policy results come second. (54)

Friends and Neighbors

Partisans in America would prefer to spend time with their own kind. (55)

A Frightful Despotism

George Washington, in his farewell address of 1796, warned the new nation about “the expedients of party.” He was concerned that if the nation divided itself into distinct parties, the priorities of the new government would focus on those parties, rather than on loyalty to the nation itself. He called this partisan loyalty “a frightful despotism.” (59)

[via: See the full transcript pasted below]

He warned that his factionalism, once sent in motion, could cause citizens to misrepresent the opinions of other citizens, and could cause fellow citizens to consider each other as enemies, even as the nation itself was struggling to form. (60)

However, while American partisanship has existed since Washington left office, the current brand differs in nature from what Washington may have expected. This is because the factionalism that Washington feared is not only applicable to partisan teams. People form factions in all sorts of dimensions. We have long known that religion, race, and even sports-team affiliations have driven people into factions, set against each other along a dividing line. Partisanship may be necessary for government to organize and assist its citizens in decision-making. The problem arises when partisanship implicitly evokes racial, religious, and other social identities. … It is this social dimension of the partisan divide that makes it far easier for individual partisans to dehumanize their political opponents. (60)

| Social contact and shared social identities are the things that allow individuals to understand each other and tolerate differences in opinion. As those connections grow scarce, the effects of party no longer affect parties alone. Partisan battles become social and cultural battles, as well as political ones. (60)

FIVE / Socially Sorted Parties

When multiple identities align, Brewer and her colleagues found, people are less tolerant, more biased, and feel angrier at the people in their outgroups. (61)

Magnified Ingroup Bias

This is the American identity crisis. Not that we have partisan identities, we’ve always had those. The crisis emerges when partisan identities fall into alignment with other social identities, stoking our intolerance of each other to levels that are unsupported by our degrees of political disagreement. (63)

The traditional understanding in political science is that sorting is simply the alignment between party and ideology. I argue that a number of additional social identities can be involved as well, as was demonstrated in chapter 2. (63)

Warmer Feelings

ANES Results

YouGov Results and the Social-Sorting Measure

The Role of Issues

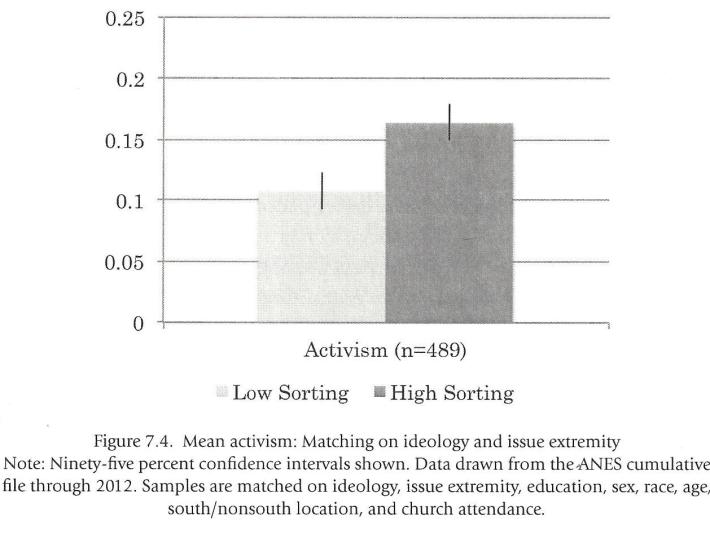

Matching

Matching is a particularly strong test of the effect of sorting because it takes a large sample of people…and simulates the random assignment of sorting to the population. In essence, this method makes it possible to pretend that each respondent is part of an experiment in which they are randomly assigned to a level of sorting. It does this by matching as many respondents as possible so that they are nearly identical in their ideology, issue extremity, political knowledge, education, age, sex, race, geographical location, and religiosity. This group of matched respondents is then divided into two groups, with the only measured difference between them being the level of sorting, either low or hight, depending on whether respondents score above or below the median value of sorting. (68)

| Once he matched sample is divided into low and high levels of sorting, I look at the differences between them in how warmly they feel toward the two parties. (68)

As partisanship moves into alignment with ideological identity, even when little else changes, partisan prejudice increases. People who are identical in their demographics, knowledge, issue positions, and ideological identity become significantly more biased when their party is aligned with their ideology. … Even when these citizens have a great deal in common sorting alone is able to drive their opinions of the two parties apart. (70)

Friends and Neighbors

If any grounds can be found for political harmony in American politics, it will not be the common ground of shared policy opinions. … Partisanship can drive significant levels of partisan prejudice, but, when our social identities line up behind our parties, our prejudices expand beyond what (72) partisanship can do on its own. (73)

We are not dealing with normal partisan bickering. … This social sorting has created, in essence, two megaparties, whose members dislike and avoid their political opponents, even when they live next door. (73)

Sorting and Policy Bias

A Pew poll from June 2013 found that, under Republican president George W. Bush, 38 percent more Republicans than Democrats believed that NSA surveillance programs were acceptable, while under Democratic president Barack Obama, Republicans were 12 percent less supportive of NSA surveillance than Democrats. …the influence of party loyalty is capable of reversing a single person’s well-argued issue position without them even realizing it. (74)

Political scientists have long known that partisan identities can affect our policy attitudes and our feelings about political contests. What is new here is the idea that partisan identities are only part of the story. The sorting that has often been recognized as a simple realignment of identities has in fact been able to motivate substantially larger levels of partisan bias than partisanship alone could do. (76)

Unfortunately, this is not normatively useful for democratic representation. The American system of democracy, as it grows increasingly socially polarized, will rely less on policy preferences and more on knee-jerk “evaluations” that should rightfully be called partisan prejudice. (76)

Is This Polarization?

…it is possible for Americans to be socially polarized even when their policy positions are not, or when those policy attitudes are relatively less polarized. (77)

SIX / The Outrage and Elation of Partisan Sorting

The anecdotes of partisan rancor and vitriol don’t seem to be simply isolated events. There has been a modest but increasing trend toward angrier American politics. (82)

Americans are not only angrier at their political opponents, they are also happier with their own team’s candidates. (82)

Why Are We So Emotional?

As elections grow longer–and political media coverage explains governing as a constant competition between Democrats and Republicans–partisans are inundated with messages that their group is in the midst of a fight for superiority over the outgroup. (83)

Intergroup emotions theory (an outgrowth of social identity theory) has found that strongly identified group members react with stronger emotions, particularly anger and enthusiasm, to group threats (Mackie, Devos, and Smith 2000). … These are natural psychological reactions to group competition, driven not by practical thoughts about the concrete outcomes of an intergroup competition but by evolutionarily advantageous reactions to group competition and threat. (83)

In 1994, Nyla Branscombe and Daniel Wann conducted a study in which they asked people to watch the movie Rocky IV. For some respondents, they altered the movie so that, in the end, Rocky is defeated by the Russian fighter, Ivan Drago. In this condition, those people who felt most closely identified with being American took severe hits to their own self-esteem. They felt very negatively about themselves after watching Rocky lose. But they were then given a chance to express their levels of distrust and dislike of Russians in general. Those who did this, who expressed many kinds of negative feelings about Russians, restored their self-esteem. These people felt better about themselves by making insulting judgments about their Russian outgroup. Imagine these effects, now, in terms of partisan competition. When partisans lose an election, they take a hit to their self-esteem, which is wrapped up in their partisan identity. One effective way of soothing this damage is to lash out at partisan opponents. (84)

When multiple identities are strongly aligned, a threat to one identity affects the status of multiple other identities. (85)

Why Do Emotions Matter?

…affective intelligence theory,… This theory argued that it was not sufficient to study the simple difference between positive and negative (valence) emotions and that far more information could be obtained if researchers looked at different types of emotions within each category–particularly in the category of negative emotions. They determined that the difference between anger and anxiety was significant, especially when looking at political behavior. (85)

Anxiety was found to lead to more thoughtful processing of information, while anger led to more reliance on easily available cues such as social identities. (86)

…feelings of anger in white Americans push them to think in more racial terms. (86)

The key point, for the purposes of this book, is that anger and enthusiasm are the primary emotional drivers of political action, and they are not drivers of thoughtful processing of information. (86)

Evidence from a Panel Study

Sorting or Party Identity?

Matching

Figure 6.6. Percent angry at the outgroup candidate in matched sample

Note: Data drawn from ANES cumulative file through 2012. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals shown. Respondents matched on ideological identification, issue extremity, education, sex, race, age, southern location, and church attendance. Low sorting and high sorting are divided by cutting the sorting score at its median.

Evidence from an Experiment

Experimental Results

Figure 6.9. Predicted angry reactions to messages

Note: Bars represent the predicted values of anger at each level of issue extremity, partisan identity, or sorting. Originating regressions are shown in appendix table 1.9. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals shown.

These data suggest that Americans are not growing increasingly angry because the best-sorted identities drive the highest levels of anger. They are growing angrier because the people who tend to respond without anger (those with cross-cutting identities) are disappearing. As the sorting seen in chapter 3 continues, the people who have the best chance of remaining calm in the face of political conflict are shrinking as a proportion of the electorate. (99)

Obstructive Anger

The more sorted we become, the more emotionally we react to normal political events, and the more cross-cutting our identities, the more calmly we respond. (100)

…hatred and anger, and the absence of positive intergroup sentiments and moral sentiments of guilt or shame, may be an important obstacle both to the type of interest-based agreements that would benefit all concerned and to the type of relationship-building programs that can humanize adversaries and create the trust necessary for more comprehensive agreements. Indeed, trying to produce such agreement through careful crafting of efficient trades of concessions, without attending to relational barriers may be an exercise in futility. – Kahn et al. (2016)

Our emotional relationships with our opponents must be addressed before we can hope to make the important policy compromises that are required for governing. (101)

SEVEN / Activism for the Wrong Reasons

I do not argue that all political participation is bad for democracy. What I do argue is that the makeup of the electorate matters. (102)

Changing cross-cut voters into well-sorted voters is not necessarily a net good for a functioning democracy, particularly if the well-sorted are more likely to vote. The well-sorted voters are more likely to be active on behalf of their identities and emotions, which drive them consistently in the direction of voting that is less responsive to changing conditions and events. (103)

A Brief History of Participation

Although the changes over time have been small, political action has increased significantly in recent years. (104)

Figure 7.2. Percentage of US population reporting having participated in each political activity

Note: Data drawn from the ANES cumulative file through 2012, weighted. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals shown.

The types of political engagement that are increasing are social engagements, and they occur most frequently among those who are in politically aware social networks. (107)

Identity-Driven Action

Social psychologists have already discovered that when people identify with a group of other people they are more likely to take political action on behalf of their group, particularly when that group is under threat. (107)

People participate not so much because of the outcomes associated with participation but because they identify with the other participants…participation generated by the identity pathway is a form of automatic behavior, whereas participation brought forward by the instrumental pathway is a form of reasoned action. – Klandermans (2003) (687)

[We] compared the effects of what we called an “expressive” partisan identity to the effects of an “instrumental” partisan identity. In other words, we measured whether social identification with a party drove more political action than issue-based identification with a party. We found that partisan identity was a significantly more powerful predictor of political action than an issue-based measure. (108)

Partisan-Ideological Sorting

American partisans are more willing to participate in politics when they are well sorted, no matter what their issue positions happen to be. This is political tribalism driving action. We are growing more politically engaged on behalf of our team spirit. (111)

Social Sorting and Activism

Issue-Driven Action

The Case of Abortion Attitudes

So, without any change in beliefs about abortion, the people who feel socially connected to the pro-choice or pro-life groups are promising significantly more political activism than those who don’t feel socially connected. (119)

Injustice, wrong, injury excites the feeling of resentment, as naturally and necessarily as frost and ice excite the feeling of cold, as fire excites heat, and as both excite pain. A man may have the faculty of concealing his resentment, or suppressing it, but he must and ought to feel it. Nay he ought to indulge it, to cultivate it. It is a duty. His person, his property, his liberty, his reputation are not safe without it. He ought, for his own security and honour, and for the public good, to punish those who injure him. … It is the same with communities. They ought to resent and to punish.

– John Adams, diary entry of March 4, 1776, one month before Lexington and Concord (quoted in Philbrick 2013)

…the emotions strong partisans experience help them to bypass individual-level utility calculations and take action on behalf of their party – Eric Groenendyk and Antoine Banks, 2014

[Anger and enthusiasm] have been labeled “approach emotions”. (122)

Without threat to a social group, members are less likely to derogate outgroups, and they have less of a motivation to improve the status of the group. Exposure to a threatening message does, overall, increase activism. (124)

But Don’t We Want an Active Electorate?

“I used to spend ninety per cent of my constituent response time on people who call, e-mail, or send a letter, such as, ‘I really like this bill, H.R. 123,’ and they really believe in it because they heard about it through one of the groups that they belong to, but their view was based on actual legislation,” Nunes said. “Ten percent were about ‘Chemtrails from airplanes are poisoning me’ to every other conspiracy theory that’s out there. And that has essentially flipped on its head.” The overwhelming majority of his constituent mail is now about the far-out ideas, and only a small portion is “based on something that is mostly true.” He added, “It’s dramatically changed politics and politicians, and what they’re doing.”

– Devin Nunes, Republican congressman from California (quoted in Lizza 2015)

Activism may have increased over the last few decades, but this is not necessarily a responsible, outcome-based participation. As Republican congressman Devin Nunes told New Yorker reporter Ryan Lizza in 2015, the types of people who reach out to him (a form of participation) are increasingly ignorant of the actual policies they wish to see enacted. They are participating, but they are doing so on the basis of misinformation and ill-formed ideas. (125)

The fact that action occurs because it simply feels good to act is not a great shining light of our contemporary democracy. (125)

Our actual opinions–the intensity of our attitudes–can’t compel the same sort of political activism that our simple sense of social connection can. (126)

…not only does a strong partisan identity drive political action, including voting, but the act of voting also drives increasingly strong identification with the party. Therefore, the more we feel partisan, the more we vote, and the more we vote, the more partisan we feel. It is a self-reinforcing cycle. (126)

While activism is generally a desirable element of a functioning democracy, blind activism is not. (126)

EIGHT / Can We Fix It?

What Happens to a Sorted Nation?

Robert Dahl describes the original concept of parties as “a current of political opinion, rather than an organized institution.” (128)

Never before or since in American history has the pattern of moderate conflict with crosscutting divisions been so fully transformed into the pattern of severe conflict and polarization” – Dahl (1981) (321)

How Social Science Deals with Intergroup Conflict

Contact Theory

See that man over there?

Yes.

Well, I hate him.

But you don’t know him.

That’s why I hate him.

-Cordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice

…certain types of social contact can reduce prejudice between groups. … Optimally, according to Allport, this contact would meet four conditions. It would occur (1) among groups of equal status who (2) have common goals, (3) no competition between them, and (4) the support of relevant authorities. (130)

In terms of reducing American partisan prejudice, contact theory would send Democrats and Republicans into the same social arenas and ask them to simply see each other with a calm and friendly set of eyes. (131)

Social Norms

One way that outright partisan prejudice may be addressed is for the parties themselves to establish new norms for partisan behavior. (132)

What if the leaders of the Democratic and Republican parties decided to take on a tolerant rhetoric toward the opposing team? What if party prototypes started discussing real differences rather than demonizing their opponents? What if party opinion leaders (of both parties) started talking about politics by commending compromise and acknowledging the humanity and validity of the opposing team? (133)

Superordinate Goals

…goals that go beyond group boundaries and include both groups,… (133)

With the decline in trust of outgroup partisans, superordinate goals are possibly no longer powerful enough to bring the parties together. Brewer (2001a) points out that “when intergroup attitudes and relations have moved into the realm of outgroup hate or overt conflict,…the prospect of superordinate common group identity may constitute a threat rather than a solution…when intense distrust has already developed, common group identities are likely to be seen as threats (or opportunities) for domination and absorption. In this case, the prescription for conflict reduction may first require protection of intergroup boundaries and distinct identities” (36). (134)

Self-Affirmation

According to theory from social psychology, there is good reason to believe that these voters are suffering from damaged self-esteem, driven by either a lack of economic opportunity, a fear of culturally changing country, or some combination thereof. Those with damaged self-esteem normally look for a way to enhance their self-image. One powerful place to find such a thing is a person’s group identity, which provides an alternate way for individuals to feel highly esteemed. (135)

The good news is that Cohen et al. (2007 have found that simply reminding a person of their own self-worth, a technique called self-affirmation, can significantly reduce extremism and ideological closed-mindedness. (236)

Demographic Trends

When a group’s status is low,…a group member has three choices. A Group member can (1) exit the group, (2) grow increasingly creative about how to describe group status, or (3) fight to change the group’s status in society. (138)

Rift in One Party: An Unsorting

It is reasonable to argue that one major reason for the period of partisan dealignment in the 1970s and 1980s had a lot to do with the flight of southern conservatives from the Democratic Party. (139)

Where Does This Leave Us?

I have taken the position that the social sorting of the American electorate has been, on balance, normatively bad for American democracy. … I maintain that an electorate that is emotionally engaged and politically activated on behalf of prejudice and misunderstanding is not an electorate that produces positive outcomes. … As long as a social divide is maintained between the parties, the electorate will behave more like a pair of warring tribes than like the people of a single nation, caring for their shared future. (141)

Transcript of President George Washington’s Farewell Address (1796)

Friends and Fellow Citizens:

The period for a new election of a citizen to administer the executive government of the United States being not far distant, and the time actually arrived when your thoughts must be employed in designating the person who is to be clothed with that important trust, it appears to me proper, especially as it may conduce to a more distinct expression of the public voice, that I should now apprise you of the resolution I have formed, to decline being considered among the number of those out of whom a choice is to be made.

I beg you, at the same time, to do me the justice to be assured that this resolution has not been taken without a strict regard to all the considerations appertaining to the relation which binds a dutiful citizen to his country; and that in withdrawing the tender of service, which silence in my situation might imply, I am influenced by no diminution of zeal for your future interest, no deficiency of grateful respect for your past kindness, but am supported by a full conviction that the step is compatible with both.

The acceptance of, and continuance hitherto in, the office to which your suffrages have twice called me have been a uniform sacrifice of inclination to the opinion of duty and to a deference for what appeared to be your desire. I constantly hoped that it would have been much earlier in my power, consistently with motives which I was not at liberty to disregard, to return to that retirement from which I had been reluctantly drawn. The strength of my inclination to do this, previous to the last election, had even led to the preparation of an address to declare it to you; but mature reflection on the then perplexed and critical posture of our affairs with foreign nations, and the unanimous advice of persons entitled to my confidence, impelled me to abandon the idea.

I rejoice that the state of your concerns, external as well as internal, no longer renders the pursuit of inclination incompatible with the sentiment of duty or propriety, and am persuaded, whatever partiality may be retained for my services, that, in the present circumstances of our country, you will not disapprove my determination to retire.

The impressions with which I first undertook the arduous trust were explained on the proper occasion. In the discharge of this trust, I will only say that I have, with good intentions, contributed towards the organization and administration of the government the best exertions of which a very fallible judgment was capable. Not unconscious in the outset of the inferiority of my qualifications, experience in my own eyes, perhaps still more in the eyes of others, has strengthened the motives to diffidence of myself; and every day the increasing weight of years admonishes me more and more that the shade of retirement is as necessary to me as it will be welcome. Satisfied that if any circumstances have given peculiar value to my services, they were temporary, I have the consolation to believe that, while choice and prudence invite me to quit the political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.

In looking forward to the moment which is intended to terminate the career of my public life, my feelings do not permit me to suspend the deep acknowledgment of that debt of gratitude which I owe to my beloved country for the many honors it has conferred upon me; still more for the steadfast confidence with which it has supported me; and for the opportunities I have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable attachment, by services faithful and persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my zeal. If benefits have resulted to our country from these services, let it always be remembered to your praise, and as an instructive example in our annals, that under circumstances in which the passions, agitated in every direction, were liable to mislead, amidst appearances sometimes dubious, vicissitudes of fortune often discouraging, in situations in which not unfrequently want of success has countenanced the spirit of criticism, the constancy of your support was the essential prop of the efforts, and a guarantee of the plans by which they were effected. Profoundly penetrated with this idea, I shall carry it with me to my grave, as a strong incitement to unceasing vows that heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence; that your union and brotherly affection may be perpetual; that the free Constitution, which is the work of your hands, may be sacredly maintained; that its administration in every department may be stamped with wisdom and virtue; that, in fine, the happiness of the people of these States, under the auspices of liberty, may be made complete by so careful a preservation and so prudent a use of this blessing as will acquire to them the glory of recommending it to the applause, the affection, and adoption of every nation which is yet a stranger to it.

Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But a solicitude for your welfare, which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger, natural to that solicitude, urge me, on an occasion like the present, to offer to your solemn contemplation, and to recommend to your frequent review, some sentiments which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all-important to the permanency of your felicity as a people. These will be offered to you with the more freedom, as you can only see in them the disinterested warnings of a parting friend, who can possibly have no personal motive to bias his counsel. Nor can I forget, as an encouragement to it, your indulgent reception of my sentiments on a former and not dissimilar occasion.

Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.

The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that, from different causes and from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens, by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together; the independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.

But these considerations, however powerfully they address themselves to your sensibility, are greatly outweighed by those which apply more immediately to your interest. Here every portion of our country finds the most commanding motives for carefully guarding and preserving the union of the whole.

The North, in an unrestrained intercourse with the South, protected by the equal laws of a common government, finds in the productions of the latter great additional resources of maritime and commercial enterprise and precious materials of manufacturing industry. The South, in the same intercourse, benefiting by the agency of the North, sees its agriculture grow and its commerce expand. Turning partly into its own channels the seamen of the North, it finds its particular navigation invigorated; and, while it contributes, in different ways, to nourish and increase the general mass of the national navigation, it looks forward to the protection of a maritime strength, to which itself is unequally adapted. The East, in a like intercourse with the West, already finds, and in the progressive improvement of interior communications by land and water, will more and more find a valuable vent for the commodities which it brings from abroad, or manufactures at home. The West derives from the East supplies requisite to its growth and comfort, and, what is perhaps of still greater consequence, it must of necessity owe the secure enjoyment of indispensable outlets for its own productions to the weight, influence, and the future maritime strength of the Atlantic side of the Union, directed by an indissoluble community of interest as one nation. Any other tenure by which the West can hold this essential advantage, whether derived from its own separate strength, or from an apostate and unnatural connection with any foreign power, must be intrinsically precarious.

While, then, every part of our country thus feels an immediate and particular interest in union, all the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means and efforts greater strength, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger, a less frequent interruption of their peace by foreign nations; and, what is of inestimable value, they must derive from union an exemption from those broils and wars between themselves, which so frequently afflict neighboring countries not tied together by the same governments, which their own rival ships alone would be sufficient to produce, but which opposite foreign alliances, attachments, and intrigues would stimulate and embitter. Hence, likewise, they will avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty. In this sense it is that your union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear to you the preservation of the other.

These considerations speak a persuasive language to every reflecting and virtuous mind, and exhibit the continuance of the Union as a primary object of patriotic desire. Is there a doubt whether a common government can embrace so large a sphere? Let experience solve it. To listen to mere speculation in such a case were criminal. We are authorized to hope that a proper organization of the whole with the auxiliary agency of governments for the respective subdivisions, will afford a happy issue to the experiment. It is well worth a fair and full experiment. With such powerful and obvious motives to union, affecting all parts of our country, while experience shall not have demonstrated its impracticability, there will always be reason to distrust the patriotism of those who in any quarter may endeavor to weaken its bands.

In contemplating the causes which may disturb our Union, it occurs as matter of serious concern that any ground should have been furnished for characterizing parties by geographical discriminations, Northern and Southern, Atlantic and Western; whence designing men may endeavor to excite a belief that there is a real difference of local interests and views. One of the expedients of party to acquire influence within particular districts is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heartburnings which spring from these misrepresentations; they tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection. The inhabitants of our Western country have lately had a useful lesson on this head; they have seen, in the negotiation by the Executive, and in the unanimous ratification by the Senate, of the treaty with Spain, and in the universal satisfaction at that event, throughout the United States, a decisive proof how unfounded were the suspicions propagated among them of a policy in the General Government and in the Atlantic States unfriendly to their interests in regard to the Mississippi; they have been witnesses to the formation of two treaties, that with Great Britain, and that with Spain, which secure to them everything they could desire, in respect to our foreign relations, towards confirming their prosperity. Will it not be their wisdom to rely for the preservation of these advantages on the Union by which they were procured ? Will they not henceforth be deaf to those advisers, if such there are, who would sever them from their brethren and connect them with aliens?

To the efficacy and permanency of your Union, a government for the whole is indispensable. No alliance, however strict, between the parts can be an adequate substitute; they must inevitably experience the infractions and interruptions which all alliances in all times have experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth, you have improved upon your first essay, by the adoption of a constitution of government better calculated than your former for an intimate union, and for the efficacious management of your common concerns. This government, the offspring of our own choice, uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.

All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common counsels and modified by mutual interests.

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Towards the preservation of your government, and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite, not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles, however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect, in the forms of the Constitution, alterations which will impair the energy of the system, and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited, remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of governments as of other human institutions; that experience is the surest standard by which to test the real tendency of the existing constitution of a country; that facility in changes, upon the credit of mere hypothesis and opinion, exposes to perpetual change, from the endless variety of hypothesis and opinion; and remember, especially, that for the efficient management of your common interests, in a country so extensive as ours, a government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is indispensable. Liberty itself will find in such a government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest guardian. It is, indeed, little else than a name, where the government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.

I have already intimated to you the danger of parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but, in those of the popular form, it is seen in its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy.

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight), the common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of the government and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true; and in governments of a monarchical cast, patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency, it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose. And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion, to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.