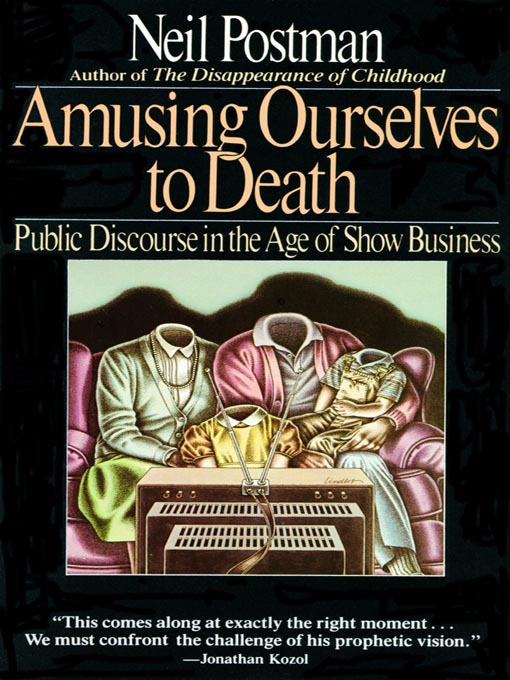

Neil Postman. Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Penguin Books, 1985. (183 pages)

Forward

This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right. (viii)

Part I

1. The Medium Is the Metaphor

…economics is less a science than a performing art. (5)

In America, the least amusing people are its professional entertainers. (5)

We are all, as Huxley says someplace, Great Abbreviators, meaning that none of us has the wit to know the whole truth, the time to tell it if we believed we did, or an audience so gullible as to accept it. (6)

…all culture is a conversation or, more precisely, a corporation of conversations, conducted in a variety of symbolic modes. (6)

…on television, discourse is conducted largely through visual imagery, which is to say that television gives us a conversation in images, not words. The emergency of the image-manager in the political arena and the concomitant decline of the speech writer attest to the fact that television demands a different kind of content from other media. You cannot do political philosophy on television. Its form works against the content. (7)

To say it, then, as plainly as I can, this book is an inquiry into and a lamentation about the most significant American cultural fact of the second half of the twentieth century: the decline of the Age of Typography and the ascendancy of the Age of Television. This change-over has dramatically and irreversibly shifted the content and meaning of public discourse, since two media so vastly different cannot accommodate the same ideas. As the influence of print wanes, the content of politics, religion, education, and anything else that comprises public business must change and be recast in terms that are most suitable to television. (8)

I believed then, as I believe now, that he [Marshall McLuhan] spoke in the tradition of Orwell and Huxley — that is, as a prophesier, and I have remained steadfast to his teaching that the clearest way to see through a culture is to attend to its tools for conversation. (8)

…it is, I believe, a wise and particularly relevant supposition that the media of communication available to a culture are a dominant influence on the formation of the culture’s intellectual and social preoccupations. (9)

For although culture is a creation of speech, it is recreated anew by every medium of communication — form painting to hieroglyphs to the alphabet to television. (10)

Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as man’s symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves man is in a sense constantly conversing with himself. He has so enveloped himself in linguistic forms, in artistic images, in mythical symbols or religious rites that he cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of [an] artificial medium. – Ernst Cassirer

In Mumford’s great book Technics and Civilization, he shows how, beginning in the fourteenth century, the clock made us into time-keepers, and then time-savers, and now time-servers. In the process, we have learned irreverence toward the sun and the seasons, for in a world made up of seconds and minutes, the authority of nature is superseded. …Eternity ceased to serve as the measure and focus of human events. And thus, though few would have imagined the connection, the inexorable ticking of the clock may have had more to do with the weakening of God’s supremacy than all the treatises produced by the philosophers of the Enlightenment; that is to say, the clock introduced a new form of conversation between man and God, in which God appears to have been the loser. Perhaps Moses should have included another Commandment: Thou shalt not make mechanical representations of time. (11-12)

To be able to see one’s utterances rather than only to hear them is no small matter, though our education, once again, has had little to say about this. Nonetheless, it is clear that phonetic writing created a new conception of knowledge, as well as a new sense of intelligence, of audience and of posterity… (12)

No man of intelligence will venture to express his philosophical views in language, especially not in language that is unchangeable, which is true of that which is set down in written characters. – Plato

Philosophy cannot exist without criticism, and writing makes it possible and convenient to subject thought to a continuous and concentrated scrutiny. Writing freezes speech and in so doing gives birth to the grammarian, the logician, the rhetorician, the historian, the scientists — all those who must hold language before them so that thy can see what it means, where it errs, and where it is leading. (12)

I bring all of this up because what my book is about is how our own tribe is undergoing a vast and trembling shift from the magic of writing to the magic of electronics. What I mean to point out here is that the introduction into a culture of a technique such as writing or a clock is not merely an extension of man’s power to bind time but a transformation of his way of thinking — and, of course, the content of his culture. (13)

…our languages are our media. Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture. (15)

2. Media as Epistemology

It is my intention in this book to show that a great media-metaphor shift has taken place in America, with the result that the content of much of our public discourse has become dangerous nonsense. With this in view, my task in the chapters ahead is straightforward. I must, first, demonstrate how, under the governance of the printing press, discourse in America was different from what it is now — generally coherent, serious and rational; and then how, under the governance of television, it has become shriveled and absurd. (16)

…we do not measure a culture by its output of undisguised trivialities but by what it claims as significant. Therein is our problem, for television is at its most trivial and, therefore, most dangerous when its aspirations are high, when it presents itself as a carrier of important cultural conversations. (16)

…I want to show that definitions of truth are derived, at least in part, from the character of the media of communication through which information is conveyed. (17)

Through resonance, a particular statement in a particular context acquires a universal significance. – Northrop Frye

You are mistaken in believing that the form in which an idea is conveyed is irrelevant to its truth. In the academic world, the published word is invested with greater prestige and authenticity than the spoken word. (21)

…the concept of truth is intimately linked to the biases of forms of expression. Truth does not, and never has, come unadorned. (22)

I hope to persuade you that the decline of a print-based epistemology and the accompanying rise of a television-based epistemology has had grave consequences for public life, that we are getting sillier by the minute. (24)

As a culture moves from orality to writing to printing to televising, its ideas of truth move with it. … Truth, like time itself, is a product of a conversation man has with himself about and through the techniques of communication he has invented. (24)

Since intelligence is primarily defined as one’s capacity to grasp the truth of things, it follows that what a culture means by intelligence is derived from the character of its important forms of communication. In a purely oral culture, intelligence is often associated with aphoristic ingenuity, that is, the power to invent compact sayings of wide applicability. The wise Solomon, we are told in First Kings, knew three thousand proverbs. In a print culture, people with such a talent are thought to be quaint at best, more likely pompous bores. In a purely oral culture, a high value is always placed on the power to memorize, for where there are no written books, the human mind must function as a mobile library. To forget how something is to be said or done is a danger to the community and a gross form of stupidity. In a print culture, the memorization of a poem, a menu, a law or most anything else is merely charming. It is almost always functionally irrelevant and certainly not considered a sign of high intelligence.

| Although the general character of print-intelligence would be known to anyone who would be reading this book, you may arrive at a reasonably detailed definition of it by simply considering what is demanded of you as you read this book. You are required, first of all, to remain more or less immobile for a fairly long time. If you cannot do this (with this or any other book), our culture may label you as anything from hyperkinetic to undisciplined; in any case, as suffering from some sort of intellectual deficiency. The printing press makes rather stringent demands on our bodies as well as our minds. Controlling your body is, however, only a minimal requirement. You must also have learned to pay no attention to the shapes of the letters on the page. You must see through them, so to speak, so that you can go directly to the meanings of the words they form. If you are preoccupied with the shapes of the letters, you will be an intolerably inefficient reader, likely to be thought stupid. If you have learned how to get to meanings without aesthetic distraction, you are required to assume an attitude of detachment and objectivity. This includes your bringing to the task what Bertrand Russell called an “immunity to eloquence,” meaning that you are able to distinguish between the sensuous pleasure, or charm, or ingratiating tone (if such there be) of the words, and the logic of their argument. But at the same time, you must be able to tell from the tone of the language what is the author’s attitude toward the subject and toward the reader. You must, in other words, know the difference between a joke and an argument. And in judging the quality of an argument, you must be able to do several things at once, including delaying a verdict until the entire argument is finished, holding in mind questions until you have determined where, when or if the text answers them, and bringing to bear on the text all of your relevant experience as a counterargument to what is being proposed. You must also be able to withhold those parts of your knowledge and experience which, in fact, do not have a bearing on the argument. And in preparing yourself to do all of this, you must have divested yourself of the belief that words are magical and, above all, have learned to negotiate the world of abstractions, for there are very few phrases and sentences in this book that require you to call forth concrete images. In a print-culture, we are apt to say of people who are not intelligent that we must “draw them pictures” so that they may understand. intelligence implies that one can dwell comfortably without pictures, in a field of concepts and generalizations. (25-16)

…in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, America was such a place, perhaps the most print-oriented culture ever to have existed. In subsequent chapters, I want to show that in the twentieth century, our notions of truth and our ideas of intelligence have changed as a result of new media displacing the old. (26)

…at no point do I care to claim that changes in media bring about changes in the structure of people’s minds or changes in their cognitive capacities. (27)

My argument is limited to saying that a major new medium changes the structure of discourse; it does so by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content — in a phrase, by creating new forms of truth-telling. I will say once again that I am no relativist in this matter, and that I believe the epistemology created by television not only is inferior to a print-based epistemology but is dangerous and absurdist. (27)

Changes in the symbolic environment are like changes in the natural environment; they are both gradual and additive at first, and then, all at once, a critical mass is achieved, as the physicists say. A river that has slowly been polluted suddenly becomes toxic; most of the fish perish; swimming becomes a danger to health. But even then, the river may look the same and one may still take a boat ride on it. In other word, even when life has been taken from it, the river does not disappear, nor do all of its uses, but its value has been seriously diminished and its degraded condition will have harmful effects throughout the landscape. It is this way with our symbolic environment. (27-28)

Typography fostered the modern idea of individuality, but it destroyed the medieval sense of community and integration. Typography created prose but made poetry into an exotic and elitist form of expression. Typography made modern science possible but transformed religious sensibility into mere superstition. Typography assisted in the growth of the nation-state but thereby made patriotism into a sordid if not lethal emotion. … as typography moves to the periphery of our culture and television takes its place at the center, the seriousness, clarity and, above all, value of public discourse dangerously declines. (29)

3. Typographic America

September 25, 1690, America’s first newspaper.

…from its beginning until well into the nineteenth century, America was as dominated by the printed word and an oratory based on the printed word as any society we know of. This situation was only in part a legacy of the Protestant tradition. As Richard Hofstadter reminds us, America was founded by intellectuals, a rare occurrence in the history of modern nations. (40-41)

The influence of the printed word in every arena of public discourse was insistent and powerful not merely because of the quantity of printed matter but because of its monopoly. (41)

4. The Typographic Mind

August 21, 1858, America’s first debate between Douglas and Lincoln.

What kind of audience was this? (44) For one thing, its attention span would obviously have been extraordinary by current standards. Is there any audience of Americans today who could endure seven hours of talk? or five? or three? Especially without pictures of any kind? Second, these audiences must have had an equally extraordinary capacity to comprehend lengthy and complex sentences aurally. (45)

People of a television culture need “plain language.” (46)

What are the implications for public discourse of a written, or typographic, metaphor? What is the character of its content? What does it demand of the public? What uses of the mind does it favor? (49)

Whenever language is the principal medium of communication — especially language controlled by the rigors of print — an idea, a fact, a claim is the inevitable result. The idea may be banal, the fact irrelevant, the claim false, but there is no escape from meaning when language is the instrument guiding one’s thought. Though one may accomplish it from time to time, it is very hard to say nothing when employing a written English sentence. What else is exposition good for? Words have very little to recommend them except as carriers of meaning. The shapes of written words are not especially interesting to look at. Even the sounds of sentences of spoken words are rarely engaging except when composed by those with extraordinary poetic gifts. If a sentence refuses to issue forth a fact, a request, a question, an assertion, an explanation, it is nonsense, a mere grammatical shell. As a consequence a language-centered discourse such as was characteristic of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America tends to be both content-laden and serious, all the more so when it takes its form from print. (50)

In a culture dominated by print, public discourse tends to be characterized by a coherent, orderly arrangement of facts and ideas. (51)

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, print put forward a definition of intelligence that gave priority to the objective, rational use of the mind and at the same time encouraged forms of public discourse with serious, logically ordered content. It is no accident that the Age of Reason was coexistent with the growth of a print culture, first in Europe and then in America. (51)

Of Whitefield, it was said that by merely pronouncing the word “Mesopotamia,” he evoked tears in his audience. Perhaps that is why Henry Coswell remarked in 1839 that “religious mania is said to be the prevailing form of insanity in the United States. (54)

The strong intellectual strain of the Congregationalists was matched by other denominations, certainly in their passion for starting colleges. The Presbyterians founded, among other schools, the University of Tennessee in 1784, Washington and Jefferson in 1802 and Lafayette in 1826. The Baptists founded, among others, Colgate (1817), George Washington (1821), Furman (1826), Denison (1832) and Wake Forest (1834). The Episcopalians founded Hobart (122), Trinity (123) and Kenyon (1824). The Methodists founded eight colleges between 1830 and 1851, including Wesleyan, Emory, and Depauw. In addition to Harvard and Yale, the Congregationalists founded Williams (1793), Middlebury (1800), Amherst (1821) and Oberlin (1833).

If this preoccupation with literacy and learning be a “form of insanity,” as Coswell said of religious life in America, then let there be more of it. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, religious thought and institutions in America were dominated by an austere, learned, and intellectual form of discourse that is largely absent from religious life today. (55-56)

The insistence on a liberal, rational and articulate legal mind was reinforced by the fact that America had a written constitution, as did all of its component states, and that law did not grow by chance but was explicitly formulated. A lawyer needed to be a writing and reading man par excellence, for reason was the principal authority upon which legal questions were to be decided. John Marshall was, of course, the great “paragon of reason, as vivid a symbol to the American imagination as Natty Bumppo.” He was the preeminent example of Typographic Man — detached, analytical, devoted to logic, abhorring contradiction. It was said of him that he never used analogy as a principal support of his arguments. Rather, he introduced most of his decisions with the phrase “It is admitted…” Once one admitted his premises, one was usually forced to accept his conclusion. (57)

Indeed, the history of newspaper advertising in America may be considered, all by itself, as a metaphor of the descent of the typographic mind, beginning, as it does, with reason, and ending, as it does, with entertainment. (58)

Advertising was, as Stephen Douglas said in another context, intended to appeal to understanding, not to passions. … In the 1890s, that context was shattered, first by the massive intrusion of illustrations and photographs, then y the nonpropositional use of language. (60)

Think of Richard Nixon or Jimmy Carter or Billy Graham, or even Albert Einstein, and what will come to your mind is an image, a picture of a face, most likely a face on a television screen (in Einstein’s case, a photograph of a face). Of words, almost nothing will come to mind. This is the difference between thinking in a word-centered culture and thinking in an image-centered culture. (61)

Almost anywhere one looks int he eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then, one finds the resonances of the printed word and, in particular, its inextricable relationship to all forms of public expression. (62)

The name I give to that period of time during which the American mind submitted itself to the sovereignty of the printing press is the Age of Exposition. Exposition is a mode of thought, a method of learning, and a means of expression. … Toward the end of the nineteenth century, for reasons I am most anxious to explain, the Age of Exposition began to pass, and the early signs of its replacement could be discerned. Its replacement was to be the Age of Show Business. (63)

5. The Peek-a-Boo World

The new idea was that transportation and communication could be disengaged from each other, that space was not an inevitable constraint on the movement of information. (64)

Thoreau, as it turned out, was precisely correct. He grasped that the telegraph would create its own definition of discourse; that it would not only permit but insist upon a conversation between Maine and Texas; and that it would require the content of that conversation to be different from what Typographic Man was accustomed to.

| The telegraph made a three-pronged attack on typography’s definition of discourse, introducing on a large scale irrelevance, impotence, and incoherence. These demons of discourse were aroused by the fact that telegraphy gave a form of legitimacy to the idea of context-free information; that is, to the idea that the value of information need not be tied to any function it might serve in social and political decision-making and action, but may attach merely to its novelty, interest, and curiosity. The telegraph made information into a commodity, a “thing” that could be bought and sold irrespective of its uses or meaning. (65)

For the most part, the information they [newspapers] provided was not only local but largely functional — tied to the problems and decisions readers had to address in order to manage their personal and community affairs. (66)

The telegraph changed all that, and with astonishing speed. Within months of Morse’s first public demonstration, the local and the timeless had lost their central position in newspapers, eclipsed by the dazzle of distance and speed. (66)

…we are thus enabled to give our readers information from Washington up to two o’clock. This is indeed the annihilation of space. – The Baltimore Patriot

It was not long until the fortunes of newspapers came to depend not on the quality or utility of the news they provided, but on how much, from what distances, and at what speed. (67)

As Thoreau implied, telegraphy made relevance irrelevant. (67)

The telegraph may have made the country into “one neighborhood,” but it was a peculiar one, populated by strangers who knew nothing but the most superficial facts about each other. (67)

How often does it occur that information provided you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would not otherwise have taken, or provides insight into some problem you are required to solve? … most of our daily news is inert, consisting of information that gives us something to talk about but cannot lead to any meaningful action. This fact is the principal legacy of the telegraph: By generating an abundance of irrelevant information, it dramatically altered what may be called the “information-action ratio.” (68)

In both oral and typographic cultures, information derives its importance from the possibilities of action. (68)

We may say then that the contribution of the telegraph to public discourse was to dignify irrelevance and amplify impotence. But this was not all: Telegraphy also made public discourse essentially incoherent. It brought into being a world of broken time and broken attention, to use Lewis Mumford’s phrase. The principal strength of the telegraph was its capacity to move information, not collect it, explain it or analyze it. (69)

The value of telegraphy is undermined by applying the tests of permanence, continuity or coherence. The telegraph is suited only to the flashing of messages, each to be quickly replaced by a more up-to-date message. Facts push other facts into and then out of consciousness at speeds that neither permit nor require evaluation. (70)

The telegraph introduced a kind of public conversation whose form had startling characteristics: Its language was the language of headlines — sensational, fragmented, impersonal. (70)

To the telegraph, intelligence meant knowing of lots of things, not knowing about them. (70)

…there is no such thing as a photograph taken out of context, for a photograph does not require one. In fact, the point of photography is to isolate images from context. (73)

The new focus on the image undermined traditional definitions of information, of news, and, to a large extent, of reality itself. (74)

…the picture forced exposition into the background, and in some instances obliterated it altogether. … For countless Americans, seeing, not reading, became the basis for believing. (74)

Together, this ensemble of electronic techniques called into being a new world — a peck-a-boo world, where now this event, now that, pops into view for a moment, then vanishes again. It is a world without much coherence or sense; a world that doe not ask us, indeed, does not permit us to do anything; a world that is, like child’s game of peek-a-boo, entirely self-contained. But like peek-a-boo, it is also endlessly entertaining. (77)

We are by now well into a second generation of children for whom television has been their first and most accessible teacher and, for many, their most reliable companion and friend. To put it plainly, television is the command center of the new epistemology. (78)

Television arranges our communications environment for us in ways that no other medium has the power to do. (78)

A myth is a way of thinking so deeply embedded in our consciousness that it is invisible. (79)

Does television shape culture or merely reflect it? …The question has largely disappeared as television has gradually become our culture. This means, among other things, that we rarely talk about television, only about what is on television — that is, about its content. (79)

Television has become, so to speak, the background radiation of the social and intellectual universe, the all-but-imperceptible residue of the electronic big bang of a century past, so familiar and so thoroughly integrated with American culture that we no longer hear its faint hissing in the background or see the flickering gray light. This, in turn, means that its epistemology goes largely unnoticed. (79)

Part II

6. The Age of Show Business

This is one use of television — as a source of illuminating the printed page. … This is another use of television — as an electronic bulletin board. … Here is still another use of television — as bookcase. (83)

…”rear-view mirror” thinking: the assumption that a new medium is merely an extension or amplification of an older one; that an automobile, for example, is only a fast horse, or an electric light a powerful candle. To make such a mistake in the matter at hand is to misconstrue entirely how television redefines the meaning of public discourse. Television does not extend or amplify literate culture. It attacks it. (84)

We might say that a technology is to a medium as the brain is to the mind. Like the brain, a technology is a physical apparatus. Like the mind, a medium is a use to which a physical apparatus is put. (84)

American television programs are in demand not because America is loved but because American television is loved. (86)

…what I am claiming here is not that television is entertaining but that it has made entertainment itself the natural format for the representation of all experience. Our television set keeps us in constant communication with the world, but it does so with a face whose smiling countenance is unalterable. The problem is not that television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining, which is another issue altogether. | To say it still another way: Entertainment is the supraideology of all discourse on television. (87)

Thinking does not play well on television. (90)

At the end, one could only applaud those performances, which is what a good television program always aims to achieve; that is to say, applause, not reflection. (91)

Our priests and presidents, our surgeons and lawyers, our educators and newscasters need worry less about satisfying the demands of their discipline than the demands of good showmanship. … There’s NO Business But Show Business. (98)

7. “Now…This”

The American humorist H. Allen Smith once suggested that of all the worrisome words in the English language, the scariest is “uh oh,” as when a physician looks at your X-rays, and with knitted brow says, “Uh oh.” I should like to suggest that the words which are the title of this chapter are as ominous as any, all the more so because they are spoken without knitted brow — indeed, with a kind of idiot’s delight. The phrase, if that’s what it may be called, adds to our grammar a new part of speech, a conjunction that does not connect anything to anything but does the opposite: separates everything from everything. As such, it serves as a compact metaphor for the discontinuities in so much that passes for public discourse in present-day America. (99)

There is no murder so brutal, no earthquake so devastating, no political blunder so costly — for that matter, no ball score so tantalizing or weather report so threatening — that it cannot be erased from our minds by a newscaster saying, “Now…this.” (99)

Consider, for example, how you would proceed if you were given the opportunity to produce a television news show for any station concerned to attract the largest possible audience. (100)

Stated in its simplest form, it is that television provides a new (or, possibly, restores an old) definition of truth: The credibility of the teller is the ultimate test of the truth of a proposition. “Credibility” here does not refer to the past record of the teller for making statements that have survived the rigors of reality-testing. It refers only to the impression of sincerity, authenticity, vulnerability or attractiveness (choose one or more) conveyed by the actor/reporter. (102)

If on television, credibility replaces reality as the decisive test of truth-telling, political leaders need not trouble themselves very much with reality provided that their performances consistently generate a sense of verisimilitude. (102)

…the average length of any story is forty-five seconds. While brevity does not always suggest triviality, in this case it clearly does. (103)

I should go so far as to say that embedded in the surrealistic frame of a television news show is a theory of anticommunication, featuring a type of discourse that abandons logic, reason, sequence and rules of contradiction. In aesthetics, I believe the name given to this theory is Dadaism; in philosophy, nihilism; in psychiatry, schizophrenia. In the parlance of the theater, it is known as vaudeville. (105)

[The idea] is to keep everything brief, not to strain the attention of anyone but instead to provide constant stimulation through variety, novelty, action, and movement. You are required … to pay attention to no concept, no character, and no problem for more than a few seconds at at time. … bite-sized is best, that complexity must be avoided, that nuances are dispensable, that qualifications impede the simple message, that visual stimulation is a substitute for thought, and that verbal precision is an anachronism. – Robert MacNeil

The result of all of this is that Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world. (106)

…in America everyone is entitled to an opinion, and it is certainly useful to have a few when a pollster shows up. But these opinions are of a quite different order from eighteenth- or nineteenth-century opinions. It is probably more accurate to call them emotions rather than opinions, which would account for the fact that they change from week to week, as the pollsters tell us. What is happening here is that television is altering the meaning of “being informed” by creating a species of information that might properly be called disinformation. … disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information — misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information — information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing. In saying this, I do not mean to imply that television news deliberately aims to deprive Americans of a coherent, contextual understanding of their world. I mean to say that when news is packaged as entertainment, that is the inevitable result. And in saying that the television news show entertains but does not inform, I am saying something far more serious than that we are being deprived of authentic information. I am saying we are losing our sense of what it means to be well informed. Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge? (107-108)

There can be no liberty for a community which lacks the means by which to detect lies. – Walter Lippmann

Lies have not been defined as truth nor truth as lies. All that has happened is that the public has adjusted to incoherence and been amused into indifference. (110-111)

I do not mean that the trivialization of public information is all accomplished on television. I mean that television is the paradigm for our conception of public information. … In presenting news to us packaged as vaudeville, television induces other media to do the same, so that the total information environment begins to mirror television. (111)

And so, we move rapidly into an information environment which may rightly be called trivial pursuit. As the game of that name uses facts as a source of amusement, so do our sources of news. It has been demonstrated many times that a culture can survive misinformation and false opinion. It has not yet been demonstrated whether a culture can survive if it takes the measure of the world in twenty-two minutes. Or if the value of its news is determined by the number of laughs it provides. (113)

8. Shuffle Off to Bethlehem

The first is that on television, religion, like everything else, is presented, quite simply and without apology, as entertainment. (116)

On these shows, the preacher is tops. God comes out as second banana. (117)

The second conclusion is that this fact has more to do with the bias of television than with the deficiencies of these electronic preachers, as they are called. … What makes these television preachers the enemy of religious experience is not so much their weaknesses but the weaknesses of the medium in which they work. (117)

Most Americans, including preachers, have difficulty accepting the truth, if they think about it at all, that not all forms of discourse can be converted from one medium to another. It is naive to suppose that something that has been expressed in one form can be expressed in another without significantly changing its meaning, texture or value. The translation makes it into something it was not. To take another example: We may find it convenient to send a condolence card to a bereaved friend, but we delude ourselves if we believe that our card conveys the same meaning as our broken and whispered words when we are present. The card not only changes the words but eliminates the context from which the words take their meaning. Similarly, we delude ourselves if we believe that most everything a teacher normally does can be replicated with greater efficiency by a micro-computer. Perhaps some things can, but there is always the question, What is lost in the translation? The answer may even be: Everything that is significant about education. (117-118)

Though it may be un-American to say it, not everything is televisible. (118)

If the delivery is not the same, then the message, quite likely, is not the same. And if the context in which the message is experienced is altogether different from what it was in Jesus’ time, we may assume that its social and psychological meaning is different, as well. (118)

Moreover, the television screen itself has a strong bias toward a psychology of secularism. The screen is so saturated with our memories of profane events, so deeply associated with the commercial and entertainment worlds that it is difficult for it to be recreated as a frame for sacred events. (120)

The executive director of the National Religious Broadcasters Association sums up what he calls the unwritten law of all television preachers:

You can get your share of the audience only by offering people something they want.

Religious programs are filled with good cheer. They celebrate affluence. Their featured players become celebrities. Though their messages are trivial, the shows have high ratings, or rather, because their messages are trivial, the shows have high ratings. (121)

I believe I am not mistaken in saying that Christianity is a demanding and serious religion. When it is delivered as easy and amusing, it is another kind of religion altogether. (121)

Television is, after all, a form of graven imagery far more alluring than a golden calf. (123)

Television’s strongest point is that it brings personalities into our hearts, not abstractions into our heads. that is why CBS’ programs about the universe were called “Walter Cronkite’s Universe.” One would think that the grandeur of the universe needs no assistance from Walter Cronkite. One would think wrong. CBS knows that Walter Cronkite plays better on television than the Milky Way. And Jimmy Swaggart plays better than God. For God exists only in our minds, whereas Swaggart is there, to be seen, admired, adored. Which is why he is the star of the show. And why Billy Graham is a celebrity, and why Oral Roberts has his own university, and why Robert Schuller has a crystal cathedral all to himself. If I am not mistaken, the word for this is blasphemy. (123)

There is no doubt, in other words, that religion can be made entertaining. The question is, By doing so, do we destroy it as an “authentic object of culture”? (124)

It is well understood at the National Council that the danger is not that religion has become the content of television shows but that television shows may become the content of religion. (124)

9. Reach Out and Elect Someone

If politics were like a sporting event, there would be several virtues to attach to its name: clarity, honesty, excellence. … If politics is like show business, then the idea is not to pursue excellence, clarity, or honesty but to appear as if you are, which is another matter altogether. (126)

The television commercial is not at all about the character of products to be consumed. It is about the character of the consumers of products. (128)

The television commercial has oriented business away from making products of value and toward making consumers feel valuable, which means that the business of business has now become pseudo-therapy. The consumer is a patient assured by psycho-dramas. (128)

The television commercial is about products only in the sense that the story of Jonah is about the anatomy of whales, which is to say, it isn’t. Which is to say further, it is about how one ought to live one’s life. (131)

Being a celebrity is quite different from being well known. (132)

For on television the politician does not so much offer the audience an image of himself, as offer himself as an image of the audience. And therein lies one of the most powerful influences of the television commercial on political discourse. (134)

This is the lesson of all great television commercials: They provide a slogan, a symbol or a focus that creates for viewers a comprehensive and compelling image of themselves. In the shift from party politics to television politics, the same goal is sought. We are not permitted to know who is best at being President or Governor or Senator, but whose image is best in touching and soothing the deep reaches of our discontent. We look at the television screen and ask, in the same voracious way as the Queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest one of all?” (135)

As Xenophanes remarked twenty-five centuries ago, men always make their gods in their own image. But to this, television politics has added a new wrinkle: Those who would be gods refashion themselves into images the viewers would have them be. (135)

What I am saying is that just as the television commercial empties itself of authentic product information so that it can do its psychological work, image politics empties itself of authentic political substance for the same reason. (136)

In the Age of Show Business and image politics, political discourse is emptied not only of ideological content but of historical content, as well. (136)

We do not refuse to remember; neither do we find it exactly useless to remember. Rather, we are being rendered unfit to remember. (137)

…we have less to fear from government restraints than from television glut; (140)

Those who run television do not limit our access to information but in fact widen it. Our Ministry of Culture is Huxleyan, not Orwellian. It does everything possible to encourage us to watch continuously. But what we watch is a medium which presents information in a form that renders it simplistic, nonsubstantive, nonhistorical and noncontextual; that is to say, information packaged as entertainment. In America, we are never denied the opporutnity to amuse ourselves. (141)

10. Teaching as an Amusing Activity

We now know that “Sesame Street” encourages children to love school only if school is like “Sesame Street.” Which is to say, we now know that “Sesame Street” undermines what the traditional idea of schooling represents. (143)

Whereas in a classroom, one may ask a teacher questions, one can ask nothing of a television screen. Whereas school is centered on the development of language, television demands attention to images. Whereas attending school is a legal requirement, watching television is an act of choice. Whereas in school, one fails to attend to the teacher at the risk of punishment, no penalties exist for failing to attend to the television screen. Whereas to behave oneself in school means to observe rules of public decorum, television watching requires no such observances, has no concept of public decorum. Whereas in a classroom, fun is never more than a means to an end, on television it is the end in itself. (143)

If the classroom now begins to seem a stale and flat environment for learning, the inventors of television itself are to blame, not the Children’s Television Workshop. We can hardly expect those who want to make good television shows to concern themselves with what the classroom is for. They are concerned with what television is for. (143)

Perhaps the greatest of all pedagogical fallacies is the notion that a person learns only what he is studying at the time. Collateral learning in the way of formation of enduring attitudes…may be and often is more important than the spelling lesson or lesson in geography or history…For these attitudes are fundamentally what count in the future. – John Dewey, Experience and Education

In other words, the most important thing one learns is always something about how one learns. (144)

Although one would not know it from consulting various recent proposals on how to mend the educational system, this point — that reading books and watching television differ entirely in what they imply about learning — is the primary educational issue in America today. America is, in fact, the leading case in point of what may be thought of as the third great crisis in Western education. (145)

One is entirely justified in saying that the major educational enterprise now being undertaken in the United States is not happening in its classrooms but in the home, in front of the television set, and under the jurisdiction not of school administrators and teachers but of network executives and entertainers. (145)

This is why I think it accurate to call television a curriculum. As I understand the word, a curriculum is a specially constructed information system whose purpose is to influence, teach, train or cultivate the mind and character of youth. Television, of course, does exactly that, and does it relentlessly. In so doing, it competes successfully with the school curriculum. By which I mean, it damn near obliterates it. (145-146)

…television’s principal contribution to educational philosophy is the idea that teaching and entertainment are inseparable. (146)

We might say there are three commandments that form the philosophy of the education which television offers.

- Thou shalt have no prerequisites

- Thou shalt induce no perplexity

- Thou shalt avoid exposition like the ten plagues visited upon Egypt

The consequences of this reorientation are to be observed not only in the decline of the potency o the classroom but, paradoxically, in the refashioning of the classroom into a place where both teaching and learning are intended to be vastly amusing activities. (148)

…what is happening here is that the content of the school curriculum is being determined by the character of television, and een worse, that character is apparently not included as part of what is studied. (153)

11. The Huxleyan Warning

There are two ways by which the spirit of a culture may be shriveled. In the first — the Orwellian — culture becomes a prison. In the second — the Huxleyan — culture becomes a burlesque. (155)

What Huxley teaches is that in the age of advanced technology, spiritual devastation is more likely to come from an enemy with a smiling face than from one whose countenance exudes suspicion and hate. (155) [VIA: Reminding me of Satan “masquerading as an angel of light” (2 Corinthians 11:14)]

When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility. (155-156)

For America is engaged int he world’s most ambitious experiment to accommodate itself to the technological distractions made possible by the electric plug. (156)

To be unaware that a technology comes equipped with a program for social change, to maintain that technology is neutral, to make the assumption that technology is always a friend to culture is, at this late hour, stupidity plain and simple. (157)

Thus, there are near insurmountable difficulties for anyone who has written such a book as this, and ho wishes to end it with some remedies for the affliction. In the first place, not everyone believes a cure is needed, and in the second, there probably isn’t any. But as a true-blue American who has imbibed the unshakable belief that where there is a problem, there must be a solution, I shall conclude with the following suggestions. (158)

We must, as a start, not delude ourselves with preposterous notions such as the straight Luddite position as outlined, for example in Jerry Mander’s Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. Americans will not shut down any part of their technological apparatus, and to suggest that they do so is to make no suggestion at all. (158)

I am not very optimistic about anyone’s taking this suggestion seriously. Neither do I put much stock in proposals to improve the quality of television programs. Television, as I have implied earlier, serves us most usefully when presenting junk-entertainment; it serves us most ill when it co-opts serious modes of discourse — news, politics, science, education, commerce, religion — and turns them into entertainment packages. We would all be better off if television got worse, not better. (159)

“The A-Team” and “Cheers” are no threat to our public health. “60 minutes,” “Eye-Witness News” and “Sesame Street” are. | The problem, in any case, does not reside in what people watch. The problem is in that we watch. The solution must be found in how we watch. (160)

For no medium is excessively dangerous if its users understand what its dangers are. It is not important that those who ask the questions arrive at my answers or Marshall McLuhan’s (quite different answers, by the way). This is an instance in which the asking of the questions is sufficient. To ask is to break the spell. (161)

In any case, the point I am trying to make is that only through a deep and unfailing awareness of the structure and effects of information, through a demystification of media, is there any hope of our gaining some measure of control over television, or the computer, or any other medium. How is such media consciousness to be achieved? There are only two answers that come to mind, one of which is nonsense and can be dismissed almost at once; the other is desperate but it is all we have.

| The nonsensical answer is to create television programs whose intent would be, not to get people to stop watching television but to demonstrate how television ought to be viewed, to show how television recreates and degrades our conception of news, political debate, religious thought, etc. (161)

The desperate answer is to rely on the only mass medium of communication that, in theory, is capable of addressing the problem: our schools. (162)

What I suggest here as a solution is what Aldous Huxley suggested, as well. And I can do no better than he. He believed with H. G. Wells that we are in a race between education and disaster, and he wrote continuously about the necessity of our understanding the politics and epistemology of media. For in the end, he was trying to tell us that what afflicted the people in Brave New World was not that they were laughing instead of thinking, but that they did not know what they were laughing about and why they had stopped thinking. (163)

— VIA —

This is an example of starting a book and finishing years later. It is also an example of how some writing borders on the quality of epic — both timeless and timely. As one of my favorite authors, Postman amazes me in that two years shy of being two decades old, the insights and prophecies of this critique have made their fulfillment, and have set the groundwork for understanding the digital age (cf. Technopoly). When it comes to cultural criticism, this is a foundational book, and one that I recommend to anyone involved in, well, the human experience.

My one unease was with Postman’s invocation of McLuhan and the claims that may have been made regarding his thesis and theories. From my understanding (an admittedly novice one), McLuhan makes radical distinctions between “mediums” and “messages,” or “technologies” and “content.” Postman’s primary stream of critique, from what I can discern, is directed more at the “message/content” than at the “medium/technology,” though it is hard to perceive at times. I found the arguments a bit convoluted at times if framed with McLuhan’s general ideas (cf. Understanding Media).

But that only leads me to read further.

Pingback: Technopoly | Notes & Review | vialogue

Pingback: West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnett, (1943) | Transcript and Highlights | vialogue

Pingback: Putin’s Revenge | Reflections & Transcript | vialogue

Pingback: Analog Church | Reflections & Notes | vialogue

Pingback: The Myth of Normal | Reflections & Notes | vialogue

Pingback: The Master And His Emissary | Reflections & Notes | vialogue